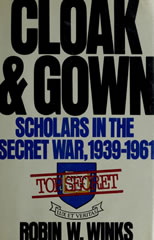

Le livre de Robin Winks Cloak and Gown: Scholars in the Secret War 1939-1961 (1987), chaudement recommandé par Michael Collins Piper, est disponible en téléchargement. Ce livre fait partie de la poignée de livres essentiels mis de l’avant par Piper dans son livre Ye Shall Know the Truth (2013):

Historians as Tools of the Global Elite

of perfidy, intrigue and ambition, as a

means of heating the imagination of

their respective nations, and incensing

them to hostilities”

—THOMAS PAINE

Many of the names will be immediately familiar. The names constitute a veritable laundry list of those whom Barnes quite correctly called “the court historians” and whom—by virtue of their wartime roles in the propaganda operations of the OSS—revolutionary statesman Thomas Paine might have been foreshadowing. He wrote of war-time propagandists in The Rights of Man declaring: “Each government accuses the other of perfidy intrigue and ambition, as a means of heating the imagination of their respective nations, and incensing them to hostilities”—not only during wartime but afterward as well. And that is why there is the need for Revisionist scholars to continue fighting to bring history into accord with the facts, wartime and postwar propaganda notwithstanding.

Spies Turned ‘Court Historians’The World War II-era Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the forerunner of the modern CIA, and also the spawning ground for a host of American academics who rose to prominence in postwar years. Most of these ex-spies—with little deviation—touted the “official” U.S.-British-Zionist intelligence propaganda version of the events that led up to the war, accounts of the war’s conduct and the twists of history that followed. Not for nothing did such independent historians as Dr. Harry Elmer Barnes refer to these characters as the “court historians.”

Above, Herbert Marcuse: It wasn’t “Hanoi Jane” Fonda or Huey Newton and the Black Panthers who invented the ideas and slogans that came to be identified with the “drop out” generation. It was Marcuse, drawing on Hegel, Marx and Sigmund Freud, who introduced the theory of “the great refusal,” meaning that individuals should reject and subvert the existing social order as repressive and conformist without waiting for a revolution. Marcuse left Germany one step ahead of the Gestapo to bring his “enlightenment” to America. He taught philosophy at various U.S. universities until his death in 1979.Among the ex-OSS spies who became influential postwar arbiters of “official” history included (1) Arthur Schlesinger Jr., (2) Carl William Blegen and (3) James Phinney Baxter.

What follows is the list of OSS-spawned academics taken from Winks’s book, including the sometimes-glowing descriptions that Winks provided:

-

- James Phinney Baxter III, president of Williams College;

- Carl Blegen, professor of history, University of Cincinnati, and a leading authority on American immigration and ethnic history;

- Crane Brinton, professor of history, Harvard University, perhaps the leading historian of ideas on the European front;

- Dr. Frederick Burkhardt, director of the American Council of Learned Societies;

- John Christopher, professor of history, University of Rochester, who with Brinton and Robert Lee Wolff wrote an extremely influential (and extremely successful) textbook, History of Civilization, immediately after the war, a text that became one of two that dominated the market for the immediate postwar generation of undergraduate students. “Brinton, Christopher and Wolff,” as the text was known, reflected the synoptic view the authors developed while in the OSS, and it would not be totally revised until 1983;

- Dr. Ray Cline, who wrote a first-rate volume in the official history of World War II and then returned to the intelligence profession. He became the CIA’s deputy director for intelligence from 1962 to 1966;

- John Clive, professor of history, Harvard University, a major figure in 19th century British studies;

- Gordon Craig, professor of history, Princeton and later Stanford universities, author of the leading books on the role of the military in German history;

- John Curtiss, professor of history, Duke University, an authority on France;

- Harold C. Deutsch, professor of history, University of Minnesota, also an important figure in the development of modern German history in the United States;

- Donald M. Dozer, professor of history, University of California, Santa Barbara, a Latin Americanist;

- Dr. Allan Evans, a medievalist from Yale who remained with the Department of State at the end of the war;

- John K. Fairbank, professor of Chinese history at Harvard University, the leading sinologist of his generation;

- Franklin L. Ford, professor of history, Harvard University, and the dean of Harvard College during the student disorders of the late 1960s;

- Felix Gilbert, historian at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, an elegant diplomatist;

- S. Everett Gleason, who worked with William Langer in the OSS and after, and returned to become the State Department’s historian;

- Moses Hadas, professor of classics, Columbia University, who wrote on the expansion of the Roman empire;

- Samuel W. Halperin, professor of history, University of Chicago, and after the war editor of The Journal of Modern History;

- Henry B. Hill, professor of history, University of Kansas, who developed British history there and later at Wisconsin;

- Hajo Holborn, Sterling professor of history, Yale University, who worked on occupation policy for Germany at the end of the war and wrote on the history of military occupation, becoming a dominant figure in the training of postwar Germanists;

- H. Stuart Hughes, professor of history, Harvard University, who moved on from where Crane Brinton had left off in European intellectual (and especially Italian) history, and unsuccessfully ran for the House of Representatives in Massachusetts;

- Sherman Kent, who left Yale to preside over ONE, the Office of National Estimates, at the CIA;

- Clinton Knox, who also left the historical profession, becoming ambassador to Guinea;

- Leonard Krieger, who returned from the OSS to become a professor at Yale and then of German intellectual history at the University of Chicago;

- William L. Langer, the outstanding European diplomatic historian of his generation;

- Val Lorwin, professor of history, University of Oregon, and the nation’s leading authority on the Low Countries;

- Herbert Marcuse, who moved from history to philosophy at Brandeis and the University of California, and from the contemplative life to that of guru to the student revolt during the war in Vietnam;

- Henry Cord Meyer, professor of history, Pomona College, another leading Germanist who left Yale for the West Coast;

- Saul K. Padover, professor at the New School for Social Research, authority on Jefferson and democratic thought, and a pioneer lecturer on American history at a wide range of universities overseas;

- Michael B. Petrovich, professor of history, University of Wisconsin, who developed Russian studies there;

- David H. Pinckney, professor of history, first at the University of Missouri and then the University of Washington, a major force in French history and, like Brinton, Craig, Fairbank, Holborn, Langer, and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., a president of the American Historical Association, perhaps the highest honor the discipline can bestow on one of its own;

- David M. Potter, professor of history, Yale University (and later at Stanford), who with Ralph Gabriel and Norman Holmes Pearson firmly established American studies at Yale;

- Conyers Read, professor of history, University of Pennsylvania, an authority on Elizabethan England and the prime mover behind the Council on Foreign Relations in Philadelphia;

- Henry L. Roberts, professor of history, Columbia University, who followed Geroid Robinson in developing a front-rank Russian studies program at that institution;

- Elspeth D. Rostow, University of Texas, who with her husband,

- Walt Whitman Rostow, worked out major interpretations on American foreign policy;

- John E. Sawyer, economic historian who left Yale to become president of Williams College and then of the Mellon Foundation;

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., professor of history, Harvard University, polymath, adviser to and historian for the Kennedys before his transition to a Schweitzer chair at the City University of New York;

- Bernadotte E. Schmitt, who after the war lived in retirement, lauded as the leading historian of the causes of WWI;

- Carl E. Schorske, professor of history at Wesleyan and then Princeton University, an authority on European intellectual history;

- Raymond Sontag, professor of history, University of California at Berkeley, the first of the old OSS team to publicly remind the student generation of the 1960s of his service and of why academics had felt it appropriate to engage in intelligence work, which he had

- Wayne S. Vucinich, professor of history, continued to do as a consultant to ONE;

- L.S. Stavrianos, professor of history, Northwestern University, who carried the idea of global history further than any other scholar, in a series of notable texts;

- Richard P. Stebbins, a man Sherman Kent felt could turn out more work of high quality than anyone else in his shop, who became director of the Council on Foreign Relations;

- Paul R. Sweet, who also remained with the State Department, in change of its official histories and archives.

- Alexander Vucinich, professor of history, San Jose State University, a leading authority on Eastern Europe; Stanford University, who covered the same waterfront;

- Paul L. Ward, who became the executive director of the American Historical Association;

- Albert Weinberg, technically a political scientist, although the author of a fine historical analysis of American imperial expansion, who remained in government work after the war;

- Robert Lee Wolff, professor of history, Harvard University, that institution’s outstanding authority on Eastern Europe;

- John H. Wuorinen, professor of history, Columbia University, who covered Scandinavia and in particular Finland;

- T. Cuyler Young, professor of archeology, Princeton University, who, with Richard Frye at Harvard (who also was in the OSS), pioneered Iranian studies in the United States.

Conseillés par Michael Collins Piper:

- Bacevich, Andrew J. – American Empire : The Realities and Consequences of US Diplomacy (2004)

- Bacevich, Andrew J. – The Limits of Power : The End of American Exceptionalism (2008)

- Bacevich, Andrew J. – The New American Militarism : How Americans Are Seduced by War (2005)

- Bacevich, Andrew J. – Washington Rules: America‘s Path to Permanent War (2010)

- Barnes, Harry Elmer – Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: A Critical Examination of the Foreign Policy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Its Aftermath (1953)

- Beard, Charles A. – A Foreign Policy for America (1940)

- Beard, Charles A. – President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War (1948)

- Beard, Charles A. – The Idea of National Interest (1934)

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin – The Israeli Connection : Who Israel Arms and Why (1987)

- Belloc, Hilaire – The Jews (1922)

- Bendersky, Joseph W. – The « Jewish Threat » : Anti-Semitic Politics of the U.S. Army (2000)

- Bennett, David H. – Demagogues in the Depression : American Radicals and the Union Party 1932-1936 (1969)

- Berg, A. Scott – Lindbergh (1988)

- Beschloss, Michael – Kennedy and Roosevelt : The Uneasy Alliance (1987)

- Birmingham, Stephen – The Grandees :The Story of America’s Sephardic Elite (1971)

- Birmingham, Stephen – Our Crowd : The Great Jewish Families of New York (1967)

- Borjesson, Kristina – Into the Buzzsaw : Leading Journalists Expose the Myth of Free Press (2002)

- Borjesson, Kristina – Quinze journalistes américains brisent la loi du silence (2003)

- Brenner, Lenni – 51 Documents. Zionist Collaboration with the Nazis (2003)

- Brenner, Lenni – Jews in America Today (1986)

- Brenner, Lenni – Le sionisme à l’âge des dictateurs (1983)

- Brenner, Lenni – Zionism in the Age of the Dictators (1983)

- Brent, Jonathan and Naumov Vladimir – Stalin’s Last Crime : The Plot Against the Jewish Doctors, 1948-1953 (2003)

- Brewton, Pete – The Mafia, CIA and George Bush : The Untold Story of America’s Greatest Financial Debacle (1992)

- Bristow, Edward J. – Prostitution and Prejudice : The Jewish Fight Against White Slavery 1870-1939 (1983)

- Buchanan, Pat – A Republic, Not an Empire : Reclaiming’s America’s Destiny (1999)

- Buchanan, Pat – Churchill, Hitler and the « Unnecessary War » : How Britain Lost Its Empire and How the West Lost the World (2009)

- Buchanan, Pat – Where the Right Went Wrong : How Neoconservatives Subverted the Reagan Revolution and Hijacked the Bush Presidency (2004)

- Burg, Avram – The Holocaust is Over : We Must Rise From Its Ashes (2008)

- Burnham, David – A Law Unto Itself : Power, Politics and the IRS (1990)

- Burnham, David – Above the Law: Secret Deals, Political Fixes and Other Misadventures of the U.S. Department of Justice (1996)

- Butler, Smedley D. – War is a Racket (1935)

- Canfield, Joseph M. – The Incredible Scofield and His Book (2005)

- Cantor, Norman – The Sacred Chain : The History of the Jews (1994)

- Carr, Stephen Alan – Hollywood and Anti-Semitism : A Cultural History up to World War II (2001)

- Carto, Willis Allison – Inside the Bilderberg Group (2008)

- Carto, Willis Allison – Populism vs Plutocracy : The Universal Struggle (1982)

- Cockburn, Alexander and St. Clair Jeffrey – Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press (1997)

- Cockburn, Andrew and Leslie – Dangerous Liaison : The Inside Story of the U.S.-Israeli Covert Relationship (1992)

- Cohen, Avner – Israel and the Bomb (1998)

- Cohen, Avner – Israël et la bombe (1998)

- Cohen, Rich – The Fish That Ate the Whale : The Life and Times of America’s Banana King (2012)

- Colby, Gerard – Du Pont: Behind the Nylon Curtain (1974)

- Cole, Wayne S. – America First : The Battle Against Intervention (1983)

- Cole, Wayne S. – Lindbergh and the Battle Against American Intervention in World War II (1974)

- Cole, Wayne S. – Roosevelt and the Isolationists, 1932-45

- Cole, Wayne S. – Senator Gerald Nye and American Foreign Relations (1980)

- Colodny, Len and Gettlin Robert – Silent Coup : The Removal of a President (1991)

- Coogan, Kevin – Dreamer of the Day : Francis Parker Yockey and the Postwar Fascist International (1999)

- Corbitt, Michael – Double Deal : The Inside Story of Murder, Unbridled Corruption and the Cop Who Was a Mobster (2003)

- Coughlin, Charles E. – Money : Questions and Answers (1936)

- Crowley, Jr. Dale – On the Wrong Side of Just About Everything, But Right About it All (2005)

- Davenport, Guiles – Zaharoff: High Priest of War (1934)

- Davis, Deborah – Katharine the Great : Katharine Graham and Her Washington Post Empire (1979)

- Deacon, Richard (aka Donald McCormick) – The Israeli Secret Service (1977)

- Denker, Henry – The Kingmaker (1972)

- Dennis, Lawrence – A Trial on Trial : The Great Sedition Trial of 1944 (1946)

- Dennis, Lawrence – Is Capitalism Doomed? (1932)

- Dennis, Lawrence – The Coming American Fascism (1936)

- Dennis, Lawrence – The Dynamics of War and Revolution (1940)

- Doenecke, Justus D. – Not to the Swift: The Old Isolationists in the Cold War Era (1979)

- Donner, Frank – The Age of Surveillance : The Aims and Methods of America’s Political Intelligence System (1981)

- Doron, Meir and Gelman Joseph – Confidential : The Life of Secret Agent Turned Hollywood Tycoon, Arnon Milchan (2011)

- Dreyfuss, Robert – Devil‘s Game: How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam (2006)

- Eisenberg, Dennis – Meyer Lansky : Mogul of the Mob (1979)

- Elias, Thomas – The Burzynski Breakthrough : The Most Promising Cancer Treatment and the Government’s Campaign to Squelch It (2002)

- Englebrecht, H.C. – The Merchants of Death : a Study of the International Armaments Industry (1934)

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose – The Secret Life of Bill Clinton : The Unreported Stories (1997)

- Faith, Nicholas – The Bronfmans : The Rise and Fall of the House of Seagram (2006)

- Farago, Ladislas – The Last Days of Patton (1981)

- Farrell, Ronald A. and Case Carol – The Black Book and the Mob : The Untold Story of the Control of Nevada’s Casinos (1995)

- Fay, Sidney B. – The Origins of the World War (1929)

- Felsenthal, Carol – Citizen Newhouse : Portrait of a Media Merchant (1998)

- Ferguson, Niall – The House of Rothschild – Volume 1 : Money’s Prophets : 1798-1848 (1999)

- Ferguson, Niall – The House of Rothschild – Volume 2 : The World’s Banker: 1849-1999 (2000)

- Findley, Paul – They Dare to Speak Out (2003)

- Friedman, Murray – The Neo-Conservative Revolution : Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy (2005)

- Friedman, Robert I. – The False Prophet : Rabbi Meir Kahane—From FBI Informant to Knesset Member (1990)

- Fritsch, Theodor – The Riddle of the Jew’s Success (1927)

- Gabler, Neal – Winchell : Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity (1994)

- Gelernter, David – Americanism : The Fourth Great Western Religion (2007)

- Giancana, Sam – Double Cross : The Explosive Inside Story of the Mobster Who Controlled America (1993)

- Ginsberg, Benjamin – The Fatal Embrace : Jews and the State (1993)

- Goldberg, Jonathan Jeremy – Jewish Power : Inside the American Jewish Establishment (1996)

- Gosch, Martin A. & Hammer Richard – The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano (1975)

- Green, Stephen – Living By the Sword : America and Israel in the Middle East 1968-1987 (1988)

- Green, Stephen – Taking Sides : America‘s Secret Relationship With a Militant Israel (1984)

- Hamilton, Alexander – The Trail of a Tradition (1926)

- Hart, Alan – Arafat, Terrorist or Peacemaker? (1984)

- Hersh, Seymour M. – The Samson Option : Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy (1991)

- Heschel, Susannah, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (2008)

- Hessing, Cahn Anne – Killing Detente : The Right Attacks the CIA (1998)

- Hinckle, Warren and Turner William W. – The Fish Is Red : The Story of the Secret War Against Castro (1981). Republished as Deadly Secrets : The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK (1991)

- Horne, Gerald – The Color of Fascism : Lawrence Dennis, Racial Passing, and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States (2006)

- Horowitz, Elliott – Reckless Rites : Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence (2006)

- Hougan, Jim – Spooks : The Haunting of America – The Private Use of Secret Agents (1978)

- Hougan, Jim – Secret Agenda: Watergate, Deep Throat and the CIA (1984)

- Jeansonne, Glenn – Gerald K. Smith : Minister of Hate (1988)

- Jeansonne, Glenn – Women of the Far-Right : The Mother‘s Movement and World War II (1996)

- Johnson, Chalmers – Blowback : The Costs & Consequences of American Empire (2000)

- Johnson, Chalmers – Dismantling the Empire : America‘s Last Best Hope (2010)

- Johnson, Chalmers – Nemesis : The Last Days of the American Republic (2007)

- Johnson, Chalmers – The Sorrows of Empire : Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic (2004)

- Karpin, Michael – The Bomb In the Basement : How Israel Went Nuclear and What That Means for the World (2006)

- Kauffman, Bill – Ain’t My America : The Long and Noble History of Anti-War Conservatism and Middle-American Anti-Imperialism (2008)

- Kauffman, Bill – America First : Its History, Culture and Politics (1995)

- Kirkpatrick, Davis James – Spying on America : The FBI’s Domestic Counterintelligence Program (1992)

- Klieman, Aaron S. – Israel’s Global Reach : Arms Sales as Diplomacy (1985)

- Knock, Thomas J. – To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson And The Quest For A New World Order (1992)

- Kotkin, Joel – Tribes: How Race, Religion and Identity Determine Success in the New Global Economy (1993)

- Krefetz, Gerald – Jews and Money : The Myths and the Reality (1982)

- Lane, Mark – Rush to Judgment: A Critique of the Warren Commission’s Inquiry into the Murder of President (2011)

- Lane, Mark – Last Word: My Indictment of the CIA in the Murder of JFK (2011)

- Larson Martin A. – Jefferson : Magnificent Populist (1985)

- Lilienthal, Alfred M. – There Goes the Middle East (1960)

- Lilienthal, Alfred M. – The Zionist Connection (1977)

- Lilienthal, Alfred M. – What Price Israel? The Other Side of the Coin : An American perspective of the Arab-Israeli conflict (1965)

- Lindbergh, Charles – The Wartime Journals of Charles Lindbergh (1978)

- Lindemann, Albert – Esau’s Tears : Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (2000)

- Long, Huey P. – Every Man a King (1933)

- Long, Huey P. – My First Days in the White House (1935)

- Louis, J.C. & Yazijian Harvey – The Cola Wars : The Story of the Global Battle Between the Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo, Inc. (1980)

- Lundberg, Ferdinand – America’s 60 Families (1937)

- Lundberg, Ferdinand – The Rich and the Super-Rich : A Study in the Power of Money Today (1968)

- Lutzweiler, David – The Praise of Folly : The Enigmatic Life and Theology of C.I. Scofield (2009)

- Mahl, Thomas E. – Desperate Deception : British Covert Operations in the United States 1939-1941 (1999)

- Maier, Thomas – Newhouse : All the Glitter, Power and Glory of America’s Richest Media Empire and the Secretive Man Behind It (1997)

- Marcus, Sheldon – Father Coughlin : The Tumultuous Life of the Priest of the Little Flower (1973)

- Marks, John D. and Marchetti Victor – CIA & The Cult of Intelligence (1974)

- McChesney, Robert W – Rich Media, Poor Democracy : Communication Politics in Dubious Times (1999)

- McCoy, Alfred – The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972). Republished as : « The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade » (1992)

- Messick, Hank – John Edgar Hoover : An Inquiry into the Life and Times of John Edgar Hoover and His Relationship to the Continuing Partnership of Crime, Business, and Politics (1972)

- Messick, Hank – Lansky (1973)

- Messick, Hank – The Silent Syndicate : Organized Crime in America (1967)

- Michael, George – Willis Carto and the American Far-Right (2008)

- Millis, Walter – Road to War : America 1914-1917 (1935)

- Moldea, Dan – Dark Victory: Ronald Reagan, MCA and the Mob (1986)

- Morris, Roger and Denton Sally – Partners in Power: The Clintons and their America (1996)

- Morris, Roger and Denton Sally – The Money and the Power : The Making of Las Vegas and Its Hold on America (2002)

- Mugridge, Ian – The View From Xanadu : William Randolf Hearst and United States Foreign Policy (1995)

- Nakhleh, Issa – The Encyclopedia of the Palestine Problem (1991)

- Newman, Peter Charles – The Bronfman Dynasty : The Rothschilds of the New World (1978)

- Novick, Peter – The Holocaust in American Life

- Olson, Lynne – Those Angry Days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and America’s Fight Over WWII (2013)

- Patman, Wright – A Primer On Money (1964)

- Patterson, James T. – Mr. Republican : A Biography of Robert A. Taft (1972)

- Pepper, William – An Act of State : The Execution of Martin Luther King (2003)

- Phillips, Kevin – American Dynasty: Aristocracy, Fortune, and the Politics of Deceit in the House of Bush (2004)

- Phillips, Kevin – American Theocracy : The Peril and Politics of Radical Religion, Oil, and Borrowed Money in the 21st Century (2007)

- Phillips, Kevin – Arrogant Capital: Washington, Wall Street and the Frustration of American Politics (1994)

- Phillips, Kevin – Bad Money : Reckless Finance, Failed Politics and the Global Crisis of American Capitalism (2008)

- Phillips, Kevin – Boiling Point : Democrats, Republicans, and the Decline of Middle Class Prosperity (1993)

- Phillips, Kevin – Post-Conservative America : People, Politics, and Ideology in a Time of Crisis (1982)

- Phillips, Kevin – The Politics of Rich and Poor : Wealth and Electorate in the Reagan Aftermath (1990)

- Phillips, Kevin – Wealth and Democracy : A Political History of the American Rich (2002)

- Pool, James and Suzanne – Who Financed Hitler? The Secret Funding of Hitler’s Rise to Power (1978)

- Press Reference – Hoover’s Guide to Media Companies (1996)

- Quigley, Carroll – Anglo-American Establishment (1981)

- Quigley, Carroll – Tragedy and Hope : A History of the World in Our Time (1974)

- Radosh, Ronald – Prophets on the Right :Conservative Critics of American Globalism (1976)

- Renfrew, Nita – Saddam Hussein (1992)

- Rochester, Anna – Rulers of America : A Study of Finance Capital (1936)

- Rodgers, Marion Elizabeth – Mencken : The American Iconoclast (2007)

- Rubin, Barry – Assimilation and Its Discontents (1995)

- Russett, Bruce – No Clear And Present Danger: A Skeptical View Of The United States Entry Into World War II (1997)

- Sandler, Martin W. – The Letters of John Fitzgerald Kennedy (2013)

- Sanning, Walter – The Dissolution of European Jewry (1983)

- Schäfer, Peter – Jesus in the Talmud (2007)

- Scheuer, Michael – Marching Toward Hell : America and Islam After Iraq (2008)

- Seale, Patrick – Abu Nidal, A Gun for Hire : The Secret Life of the World’s Most Notorious Arab Terrorist (1992)

- Seldes, George – 1000 Americans : The Real Rulers of the USA (1974)

- Shannan, Pat – One in a Million : An IRS Travesty, Pat Shannan (1999)

- Shapiro, Edward S. – A Time for Healing : American Jewry Since World War II (1992)

- Shoup, Lawrence H. & Minter William – Imperial Brain Trust : The Council on Foreign Relations and United States Foreign Policy (1977)

- Silberman, Charles E. – A Certain People : American Jews and Their Lives Today (1985)

- Silbiger, Steven – The Jewish Phenomenon: Seven Keys to the Enduring Wealth of a People (2000)

- Sklar, Holly – Trilateralism : The Trilateral Commission and Elite Planning for World Management (1980)

- Slezkine, Yuri – The Jewish Century (2004)

- Smith, Amanda – Hostage to Fortune : The Letters of Joseph Kennedy (2001)

- Smith, Amanda – Newspaper Titan : The Infamous Life and Monumental Times of Cissy Patterson (2001)

- Smith, Gerald L. K. – Besieged patriot : Autobiographical episodes exposing communism, traitorism, and Zionism from the life of Gerald L.K. Smith (1978)

- Smith, Richard Norton – The Colonel : The Life and Legend of Robert R. McCormick (1997)

- Snyder, Louis L. – The Imperialism Reader : Documents and Readings on Modern Expansionism (1962)

- Solzhenitsyn, Alexander – Two Hundred Years Together – Vol I and II (2002)

- Soljenitsyne, Alexandre – Deux siècles ensemble

- Sombart, Werner – Les juifs et la vie économique (1924)

- Sombart, Werner – The Jews and Modern Capitalism (1911)

- Stern, Malcolm H. – Americans of Jewish Descent : A Compendium of Genealogy (1958)

- Stonor, Saunders Frances – Qui mène la danse? La CIA et la guerre froide culturelle (1999)

- Stonor, Saunders Frances – The Cultural Cold War : The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (2000)

- Strauss, Feuerlicht Roberta – The Fate of the Jews : A People Torn Between Israeli Power and Jewish Ethics (1983)

- Tansill, Charles Callan – The Back Door to War : The Roosevelt Foreign Policy 1933-1941 (1952)

- Tansill, Charles Callan – America Goes to War (1938)

- Thomas, Evan – The Man to See (1991)

- Tourney, Phil – What I Saw That Day : Israel’s June 8 1967 Holocaust of US Servicemen Aboard the USS Liberty and its Aftermath (2011)

- Vidal, Gore – Dreaming War : Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta (2005)

- Vidal, Gore – Imperial America : Reflections on the Unites States of America (2005)

- Vidal, Gore – Perpetual War For Perpetual Peace : How We Got To Be So Hated (2002)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 01 – Burr (1973)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 02 – Lincoln (1984)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 03 – 1876 (1976)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 04 – Empire (1987)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 04 – Empire – FR (1987)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 05 – Hollywood (1990)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 05 – Hollywood – FR (1990)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 06 – Washington DC (1967)

- Vidal, Gore – The American Chronicle 07 – The Golden Age (2000)

- Vidal, Gore – The Decline and Fall of the American Empire (2002)

- Vidal, Gore – The Last Empire : Essays : 1992-2000 (2002)

- Von Hoffman, Nicholas – Citizen Cohn (1998)

- Waldron, Lamar – The Hidden History of the JFK Assassination (2013)

- Waldron, Lamar – Watergate : the Hidden History, Nixon, the Mafia and the CIA (2012)

- West, Nigel – The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas 1940-1945 (1999)

- White, William – The Centuries of Revolution : Democracy, Communism, Zionism (2012)

- Wilcox, Robert K. – Target : Patton – The Plot to Assassinate General George Patton (2008)

- Wilford, Hugh – The Mighty Wurlitzer : How the CIA Played America (2008)

- Williams, T. Harry – Huey Long (1969)

- Winks, Robin W. – Cloak and Gown : Scholars in the Secret War: 1939-1961 (1987)

- Wise, David – The American Police State : The Government Against the People (1976)

- Wise, Jennings – Woodrow Wilson : Disciple of Revolution (1938)

- Wolff, Michael – Rupert Murdoch : The Man Who Owns the News (2008)

Sur ce blog:

Collection audiovisuelle et livresque de Michael Collins Piper (1960-2015)

SUPERMOB: How Sidney Korshak And His Criminal Associates Became America’s Hidden Power Brokers

« Our Crowd » (« notre bande »): Les cent familles juives qui régnèrent sur New York au 19e siècle